Missy's smooth, tan legs walked on black wedges as a morning breeze gently played with her hair, a deep brown to match her eyes. Although she wasn’t always aware of it, her tongue continued to touch the small scar on her lip from when her mother won, by force, last year’s battle of which skirt she would wear on the first day of high school. On this year’s first day, Missy wore the same denim skirt, but her legs had grown two inches longer since the end of the previous year, and her chest increased about the same. This year, in trade for wearing the skirt, she handed over the lipstick to her mother after plucking it from her Coach purse. As she turned the corner, out of her mother’s view, she quickly unbuttoned the sweater that had been hiding the white cotton top that allowed the red bra to shine through. Welcome to sophomore year.

That’s Missy in about 160 words. We’ve got her hair, eyes, clothes, shoes, legs, and a scar inside her lip. Is that a character? Could be. Perhaps you find her interesting enough so far, or perhaps you’ll find this version of Missy more interesting…

That’s Missy in about 160 words. We’ve got her hair, eyes, clothes, shoes, legs, and a scar inside her lip. Is that a character? Could be. Perhaps you find her interesting enough so far, or perhaps you’ll find this version of Missy more interesting…

As each step brought Missy closer to the first day of school, her pace softened. She knew that regardless of which teachers or classes were typed on her senior-year schedule, the only factor that would determine between a good or bad day was whether or not she crossed paths with either of the boys who, according to rumors, managed to get her drunk enough to forget her own name after convincing her to sneak away from the July 4th fireworks only two months prior.

Again we have Missy, but only about 80 words. Lacking this time is anything you can “see.” No hair, eyes, clothes, shoes, or scar. Nothing in the way of the kind of character description that most readers enjoy and many writers work to deliver. But what do we really know about this “character”? Which is “better”? Which is more “descriptive”? Depends. What do you really need to know?

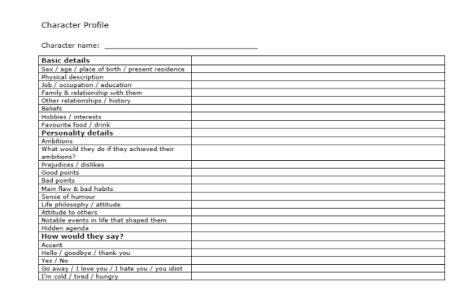

I have sat through a good handful of sessions with people who are very certain they are not only writing experts but are able to make me one as well. I have laughed each time these writing “teachers” handed me a form with boxes and lines designed to guide me into creating my character. On these forms were spaces for the exact date and city of birth, same details about immediate family, street address, nickname of the high school mascot, how many people they’ve had sex with, favorite color and movie and food, etc. Probably not the sex part, but that’s just me perverting yet another blog post, but the point is this – do you really need to know all of that information to create a good character? I don’t think so.

In Connecting Flight, a novel I wrote about a year ago that will be published in January of 2015, there were two very important characters: Chris and Ann. I did not include much about their physical descriptions because, to me, it wasn’t necessary. I wrote that Ann had bright blonde hair and a black top. Those details were important only because she was a model, and the blonde over black helped her stand out when someone spotted her in an airport. I mentioned that Chris had been teaching high school math for 15 years and no longer had the physique he once possessed from when he played first base on his college baseball team. I briefly mentioned khaki pants and sneakers, but I put nothing about hair or eye color, nothing about height or weight, not specifically.

More important to me was that Chris was a control freak, afraid of flying, had some small spots of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and was harboring guilt that he caused his 8-year old son's death as well as suspicions that his wife was having an affair. Ann was an earthy but aging model looking for one last hurrah while also suspecting her spouse of cheating. Why didn’t I focus much on their appearances?

I don’t know about you, but I don’t “read” books. Instead, I “watch” movies on paper. What I mean is that when I read a book, I have a movie playing in my head. I decide, sometimes regardless of what the author has told me, which actors I think would be good to play each character if the book were (and in my head, it is) a movie. While writing that story and watching the “movie” in my head, the part of Chris was played by Tom Hanks. Ann was played by Meg Ryan because they fit my personal vision/description for those characters, not just just in appearance but in attitude as well.

I thought about previous films I had seen. I took the Tom Hanks from Saving Private Ryan (not the soldier, just his hardened yet scared, matter-of-fact personality) and the Meg Ryan from Kate and Leopold, and they seemed like who I wanted to play the parts of Chris and Ann. As I wrote, I “saw” them performing my writing as if it were a movie, and I simply typed what I was seeing. That’s how I write, and that’s how I read.

I don’t always need to care about the character descriptions you might provide in your story. If Steve Martin or Tina Fey seem right for the part, I will ignore your description (if there is any) and see who I choose as I turn each page. If Emma Stone and Leonardo DiCaprio seem a better fit, then you can save all that work you put into your character profiles.

How much do you need to know about a character for them to become a “character”? Do you need to know exactly how old she is? Precise hair color and/or length? Height or weight? Eye color? What does it matter? That depends.

The most likely use of such a description for me would be if later in the story I needed something, a small aspect, to add a little extra dimension to the story. However, if I write all of this before beginning the story – as these writing teachers suggest – then my later additions will likely be influenced by the previously written description. Instead of prescribing that description, let it wait until you actually need to create those dimensions, and then you can tune them however necessary to fit what the story or character needs at that moment. If you create the description and background before writing your story, you might just paint yourself into a corner.

Perhaps later in the story you want to show how a girl may or may not be the daughter of a certain man. One way would be to use eye color. If a girl had Aruba Blue eyes (I did NOT make that up), but both of her parents had caramel brown, then it’s important because it might provoke a question about who her parents really might be. I only need to know how long her hair is if there’s a reason, such as if later she’s going to cut her hair and donate it to make wigs for cancer patients or obsessed with her appearance. I only need to know if she hides make up from her parents if she’s going to increase her rebelliousness and it should be foreshadowed, or perhaps if the lipstick will cause her to be mistaken as older than she actually is.

So let’s have fun. I’ll write a paragraph about a character, but there will be minimal or no physical, visual description. Then ask yourself, does it matter? Do you have enough for him to be a "character"?

For the third consecutive day, George’s alarm did not ring. He started to sit up quickly until he realized that his back would not allow him to do anything quickly. His legs trembled as one, then the other, fell over the side of the bed and reached for the floor, touching once and again before planting confidently enough. Fingers, with nails longer than most, gripped the side of the bed as he pulled himself to sit up. He was already out of breath, but it was only the beginning. The skin of his legs, naked and pale, tightened as he leaned forward, using his body weight to get closer to upright. He nearly toppled forward until reaching and catching the back of a chair next to the bed. He closed his eyes and exhaled with thanks that he wasn’t on the floor. After catching his breath and allowing some strength to return to his legs, he surveyed the room. Then, just like the previous two days, he struggled to remember where he was and why.

You might say these are only small samples, and somewhere in the rest of the story there could be the more expected kinds of physical and visual descriptions. In some cases you would be right but not always. All I need to know when I read, and all I usually write, is what is happening inside the character – not outside. Tell me what he is thinking, doing, and saying, and I can fill in the rest myself.

I have invited readers to read chapters of the aforementioned characters Chris and Ann through my 80,000 word story and then tell me two things:

- How have you imagined their ages and appearances?

- Does it matter at all?

The responses to the first question were quite varied, but the answer to the second question was rather consistent. None of the readers cared in the least. Everyone who responded, roughly 20 people, all said that they were doing exactly as I do – they imagine their own descriptions as they see fit, occasionally disregarding what writers might provide.

My suggestion is to worry more about the story, the motivations, actions, and thoughts of a character. Think of them as just pencil sketches with a brain. Make them move and think, but be sure you know why and where they are moving and what and why they are thinking. The same for pieces of the setting, like houses, cars, and rooms, just sketches. Later, if or when necessary, then you can give it all a nice coat of paint.